It has been two years since I developed and taught the course “Gender, Sex, and Religion”. I went on to use the material in my other classes on Asian Studies and the discussions on Colonialism and Social Perception. Of the cases we discussed for the course, the story of the Lavani performers and the “nautch-girls” continues to haunt me. I read Sharmila Rege’s writings extensively during the period I was preparing for this course. And “Dalit Counter-Publics and the Classroom: A Sharmila Rege Reader” was an accessible work that I decided to assign the learners in my class to read…

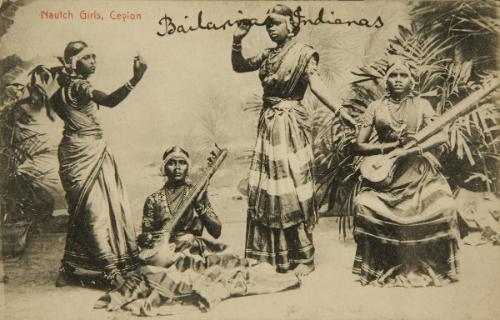

Performance arts, meant for the entertainment or leisure of the elite males in pre-Colonial South Asia, continued under the male gaze. Under such gaze, the female performers were at the mercy of their male connoisseurs or commissioners. Most (if not all) forms of dance and music moved from community-based performance to a curated spectacle geared to tantalize the audience, and thereby to objectify the performer. While this story is true for the most part, it is the performance stage that also subverted these “norms” as time went on.

In today’s short post, I wish to highlight this subversion through the presentation of gender and sexuality on stage – under a spotlight, if you will. The chapter “Hegemonic Appropriation of Sexuality: The Case of Lavani Performers of Maharashtra” with inputs by V. Geetha and Uma Chakravarty charts such a story of performance (art and gender) through the Lavani performances. Let us briefly review the central discussion, and then we will move on to my question for you.

Maharashtra traces a long history of Lavani, firstly as a showcase of beauty or “lāvaṇya” for the masses. V. Geetha and Uma Chakravarty trace the history of the performance from women’s folk songs to private “baithaks” with royal patronage. The Lavani songs also move from the subject-matter of inter-women relationships in the household (mother and daughter-in-law, co-wives, etc) to a woman pining for her lover. With this change, the performances would have likely changed their approach, and we see a plethora of new compositions with sexual innuendo enter the Lavani lexicon. While the chapter outlines sexual exploitation of the artistes, I would also point to the moments of subversion (albeit small, but not insignificant) in the art. As the female-ness of the performer continued to be objectified, we often see the Lavani compositions themselves exert soft power, where the woman would demand her wishes to be fulfilled. You might argue that the wishes in these compositions are frivolous – of new jewellery, new sari, etc. and do not amount to much. However, in a strained economy of the 18th century to which most of the compositions date to commanding a fiscal payout to the women performers at the Lavani phad would have started a quiet revolution that we see play out in modern times.

The chapter also focuses on an often understudied aspect of the subjugation of Dalit Lavani artists. The chapter argues that patriarchal caste ideology strictly regulates the sexual division of labor, and the control of female sexuality is crucial for the continuation of the caste system. The Lavani stage offered one such avenue in the 17th -18th centuries CE. On one hand, the suggestive compositions in the Lavani extended to the expectations of the patrons to teh artist’s sexual availability, and on the other, the dominant-caste elites constructed these subaltern performers as inherently salacious, “obscene,” or sexually insatiable, in contrast to the “chaste” ideal of upper-caste womanhood. This moral framing devalued the art itself and justified the exploitation of Lavani performers.

Let us return to the Lavani compositions. Shringarachi Lavani (sensual compositions) often centre around man-woman relationships, commanding a material exchange in addition to the exchange of physical pleasure. We see this trend by some degree in the compositions of post-18th century shahirs (composers) of the Kalgi line, patronised by the Marathas in Tanjore. With the references from Purāṇa literature popularized through narrative performances, these Lavani compositions utilise idioms such as Madanāca bāṇ (the arrow from Madan’s bow – akin to the simile for cupid), Ratijaṇu stana (breasts compared to those of a nymph named Rati), etc. Here, the popular imagination gets embodied as the Lavani performer. In a sense, the Lavani performer is at once the embodied meaning of the spoken word and becomes the object of desire themselves.

In modern times, the Lavani has undergone a process of “folklorization” and urban revivalism, where it is valorized as the “folk art” of Maharashtra. However, this sanitized version often excludes the hereditary, lower-caste women who are the traditional performers (often dismissed as “vulgar” or “just sex, no art”), thus erasing their histories and labor from the mainstream narrative. The efforts to situate the art within its troubled history have once again renewed a conversation on its many facets. I had the immense pleasure of learning about quiet but impactful subversions at a Lavani performance in Pune in October 2025. Some of the artists are reclaiming the art form with their caste-location. Now what remains is the battle ahead on teh perception of gender and notions of “availability”.

The reading further sparked the conversations on performance arts and narratives of prostitution. When the Imaginarium of the object of desire cracks open, and the performer becomes a commodity available for access, the boundaries between connoisseur of the arts and the art itself are breached. The chapter I linked above goes on to talk about the exploitation of the Lavani artistes, and the labelling of the performers as sexually “available” for the highest bidder at the baithaka (generally understood as a private congregation) Lavani performances. A similar fate for the dancing girls in Lucknow during the British Colonial period raised eyebrows. Howard Grace’s work on the tawaifs of Delhi and Lucknow sheds some light on this discussion.

I was thinking aloud about performing one’s gender through art and its societal repercussions, or let’s say, “feedback loop”. The ongoing question about deepfake images and videos sensationalizing snippets from performers’ repertoire raises similar questions about “breaching”. I return to the thought of breaching the boundary between the artist and their performance of a sensual or sexualized act/skit/composition. As the audience, is it not our responsibility to understand that these two are separate – the art and the artiste?

Sources for this post:

Geetha, V., & Chakravarti, U. (Eds.). (2024). Dalit Counter-publics and the Classroom: A Sharmila Rege Reader (1st ed.). Routledge India.

https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/items/12745fb2-dfb5-4dca-aa53-519788359b20

Check out further research on this topic : https://www.huronresearch.ca/courtesansofindia/

Leave a comment